Behind A Random String Generator

It starts when I play with the javascript source codes of Google Translate. There is an interesting line:

Math.floor(2147483648 * Math.random()).toString(36); |

which generates a random 6-character string, e.g. 2qa2xe.

Math.toString()When the string converted from the random number in 36 decimal, the characters are selected from $[0-9] \cup [a-z]$.

var a = 35;

a.toString(); //"35"

a.toString(2); //"100011"

a.toString(36); //"z"2147483648I found out that this magic number is $2^{31}$. Since

Math.random()returns a float between $[0,1)$,Math.floor(2147483648 * Math.random())

returns an integer between $[0, 2147483648)$. The ‘largest’ string is

zik0zj.

So in my opinion, this line is used as a light-weight random string generator, which could be used to identify the users or sessions.

For example, we want to generate a 6-character random string.

The number corresponding with the max 6 character string zzzzzz is $36^{6} - 1$

N = 6 |

With little efforts we could extend it to a full generator:

// A random string generator |

Underneath the functions

Math.random() may be the most frequently used functions, and almost all mainstream languages have built-in implementations.

Most Javascript engines use a pseudo-random number generator(PRNG), in which the random number is derived from an internal state and calculated by a fixed algorithm. Python random module also uses pseudo-random number generators with the underlying implementation in C.

I found an interesting implementation in github repository of Chrome v8, in a benchmark implementation.

// To make the benchmark results predictable, we replace Math.random |

It overrides original function and delivers a fixed sequence of “random” number, which is determined by the seed.

# the sequences are deterministic given a particular seed: |

Moreover, from the comments, we could have these inferences:

- this alternative

Math.randomis deterministic by the seed, to make sure benchmarks are measured in the same way. - the original

Math.randomshould not be 100% deterministic, at least on time-consuming performance. - this alternative should not be computationally expensive with a 32-bit internal state.

Yang Guo from V8 project has an introduction about how they upgrade from the 64-bit internal state algorithm to the new 128-bit one, called xorshift128+.

Of course the solution of adding more bits ($N$) is effective to make random numbers hard to repeat themselves (permutation cycle is $2^{N}$), but, how to get a randomly chosen seed – a pure spark?

Chaos, Uncertainty, Randomness

Predictable states are unavoidable in computers, while the chaotic universe is full of randomness around us, such as Brownian motion, the movement of atoms or molecules.

The question is how to capture it, and in an efficient way.

I heard about that in the ancient era of Windows XP, one black magic is to apply an IE plugin to access the current voice input, to get such random variables. The white-noise signals provide very reliable source and thus the JavaScript module could later use it as the unique-id. Though the details are not introduced, I believe it’s feasible.

At that time I started to think about how to capture such chaotic signals.

The article by Greg Taylor and George Cox introduces their efforts on Intel’s new random number generator. From this we learned that there have been successful trials to generate random numbers with circuits, however, the cost of energy was one of the biggest shortcomings. Their new solution was fabulous:

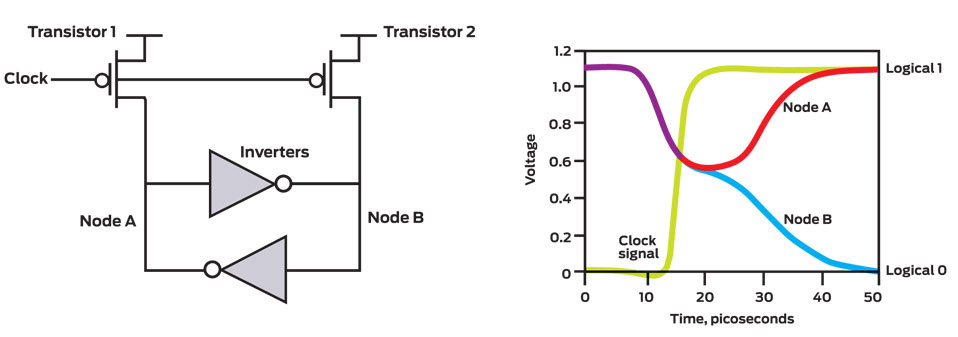

Uncertain Circuits : When transistor 1 and transistor 2 are switched on, a coupled pair of inverters force Node A and Node B into the same state [left]. When the clock pulse rises [yellow, right], these transistors are turned off. Initially the output of both inverters falls into an indeterminate state, but random thermal noise within the inverters soon jostles one node into the logical 1 state and the other goes to logical 0.

The circuits take advantage of the physically random properties of the thermal noise to generate a random binary outcome – a pure spark.

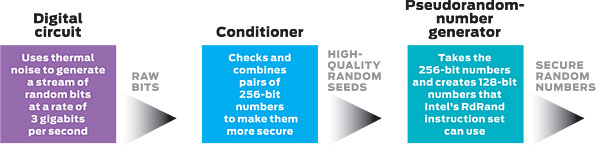

In practice, the electric features of transistors are never exactly the same, so there will be more one state than another statistically. However we require them to be almost equally distributed with 0s/1s. Given a long stream of raw bits from the circuit, a conditioner is set to monitor the frequency of 0s/1s, to fix the bias and correlation in the long term. Next, the stream from conditioner is sent to PRNG, then we will have the random number.

I feel this should be the first lesson of my bachelor study on Analog/Digital Circuits. It unveils the design of fundamental graceful hardwares for a commonly used function, and vividly points out the importance of understanding fundamental technologies. For me, it is very exciting to see such a beautiful solution, and to enjoy the progress to think deeper.

Another question just occurred to me: is such randomness related with Quantum Communication, if yes, is it taking advantage of the uncertainty in atomic level?

Aside: Random numbers in Crypto Safety

As Yang Guo points out in the blog that:

Even though xorshift128+ is a huge improvement.., it still is not cryptographically secure. For use cases such as hashing, signature generation, and encryption/decryption, ordinary PRNGs are unsuitable. The Web Cryptography API introduces window.crypto.getRandomValues, a method that returns cryptographically secure random values, at a performance cost.

Python docs also give a warning:

Warning: The pseudo-random generators of this module should not be used for security purposes. Use os.urandom() or SystemRandom if you require a cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator.

Generally, cryptographically secure means even if the attackers know the current state of this generator (or guess correctly), it’s still infeasible to get the next state with reasonable computational power.

It is very clear that they suggested using cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator CSPRNG instead of PRNG in safety-sensitive scenes.